Leadership

I practice leadership by applying the Adaptive Leadership framework to complex health system problems. This is work for situations where expertise is necessary but not sufficient, where values collide, losses are real, and progress requires learning rather than better answers. My aim is to help people stay in the work long enough to see what is actually happening, and then move carefully toward what is possible.

Learning happens when we create a holding space for difficult questions, and resist the urge for premature answers.

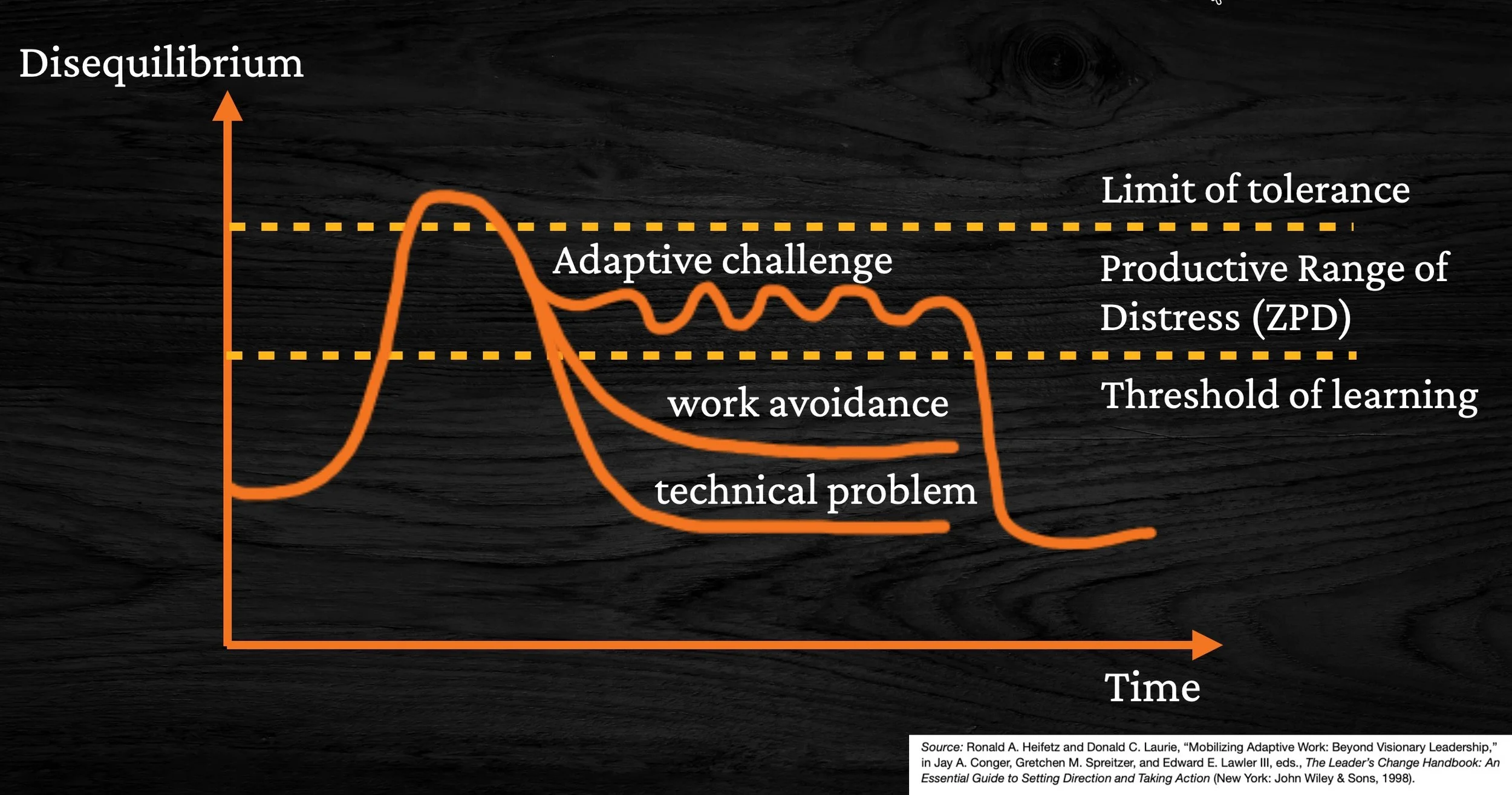

Adaptive work and the zone of productive disequilibrium

Adaptive Leadership begins with a distinction between technical and adaptive problems.

Technical problems have known definitions and known solutions. They respond to expertise, process, clearer rules, revised communication, or authority.

Adaptive problems do not. They require learning, shifts in behaviour, rebalancing loyalties, and facing loss. The problem is not primarily technical, so technical adjustments alone do not resolve it.

This is why the zone of productive disequilibrium matters. Too little heat and nothing changes. Too much heat and people shut down, polarize, or disengage. Leadership is the ongoing work of regulating that heat so learning can occur.

As Ron Heifetz puts it, exercising leadership is about disappointing people at a rate they can tolerate. The point is not to provoke. The point is to move carefully enough that the system can bear the losses required for progress.

Exercising leadership is about disappointing people at a rate they can tolerate. - R Heifetz

The holding environment

Adaptive work requires a holding environment.

A holding environment is not an emotional bubble. It is a structured container strong enough to hold tension, uncertainty, and disagreement without collapsing. It creates enough safety to stay engaged and enough honesty to surface what is real.

I think of it as a vessel. Strong enough to contain pressure. Open enough to let steam out. Stable enough that difficult truths can be spoken without the conversation becoming personal or punitive.

When a holding environment is working well, people can stay in contact with complexity. They can hear perspectives they would normally resist. They can name real losses. They can remain in the conversation long enough for something new to emerge.

Leadership is the activity of mobilizing people to do adaptive work and face the difficult reality.

Possibility, not performance

Ben Zander has influenced how I think about leadership as a human act. The question is not how to look like a leader. The question is how to create conditions where people can bring their best attention, imagination, and courage to the work in front of them.

I return often to the idea that leadership is an invitation into possibility. Possibility changes what people notice. It widens the frame. It softens defensiveness. It makes learning feel worth the risk.

This matters in healthcare, where pressure can narrow our view and urgency can replace curiosity. In those moments, a leader’s job is often to help the system breathe again.

The world of measurement is a world of scarcity. The universe of possibility is a world of abundance.

Lines of code and identity

Adaptive challenges often activate identity.

We all carry lines of code. Assumptions about who we are, what we are responsible for, what competence looks like, and what it means to be good. These lines of code usually remain invisible until the system asks us to change.

This is one reason adaptive work cannot be reduced to strategy. It touches loyalty, loss, and belonging. It raises questions like:

Who am I if I am not the expert.

What do I lose if this changes.

What part of my identity is being threatened.

What am I protecting.

Inside out leadership starts here. The work on the system is inseparable from the work on the self.

Holding despair and practicing non-defense defense

Adaptive work often brings people into contact with despair. Not dramatic despair, but the quieter kind that shows up when familiar solutions stop working, when progress feels slow, or when the cost of change becomes visible.

This is a normal part of the work. It is also the moment when leaders feel pressure to relieve discomfort. They fix. They reassure. They explain. They narrow the conversation. Or they withdraw.

The challenge is that despair is not something to eliminate. It is often a signal that people are touching something real. Something that matters. Something that cannot be solved quickly.

This is where non-defense defense becomes a leadership practice.

Non-defense defense does not mean passivity. It does not mean accepting poor behaviour or avoiding accountability. It means resisting the impulse to protect ourselves in ways that shut down learning.

It means noticing the urge to explain or correct and pausing.

It means staying with discomfort rather than escaping it.

It means listening for what is underneath the reaction.

It means keeping the work in the center rather than making it personal.

Progress often arrives through small shifts. A reaction noticed instead of acted on. A conversation held a little longer. A moment of honesty that changes how people see the problem.

A practical orientation

Across my teaching and leadership work, I use a simple but difficult to hold to orientation.

Begin with diagnosis. Stay close to reality. Look for the losses beneath the resistance. Regulate the heat. Build a holding environment that can bear honesty. Aim for small tests rather than sweeping reform.

If we leave with a clearer sense of the adaptive challenge and a few places where a small shift is possible, the work has moved.

Where to go next

If you’re interested in how these ideas show up in practice, you may want to explore the spaces where I work with them more directly. The Adaptive Leadership section goes deeper into the frameworks and habits that guide my thinking in complex systems. Lines of Code and Identity looks more closely at the inner work of leadership and how identity, loss, and loyalty shape what we are able to do. The True North Leadership Lab is where these ideas are taught and tested with learners and leaders, and the Teaching section reflects how this approach comes to life in educational settings. Each of these is a different entry point into the same question: how we learn to lead when the answers are not yet clear.